The world’s fastest data

- Author, Chris Baraniuk

- Paper, Technology Reporter

As IT upgrades go, this was about as stressful as it gets.

In February, deep in a warehouse at Cern, the Swiss home of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) — the world’s largest scientific experiment — two network engineers held their breath. And pressed a button.

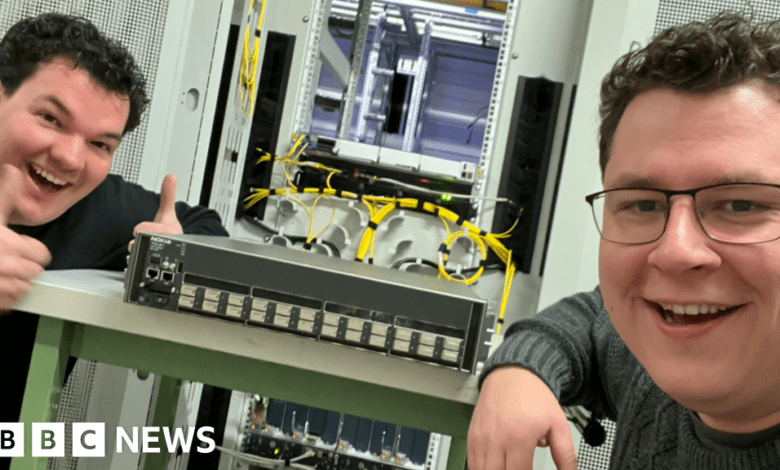

Suddenly, text on a black background appeared on a screen in front of them. It had worked. “There were high-fives involved,” recalls Joachim Opdenakker of SURF, a Dutch IT association that works for educational and research institutions. “It was super cool to see.”

He and his colleague Edwin Verheul had just set up a new data link between the LHC in Switzerland and data storage sites in the Netherlands.

A data link that could reach speeds of 800 gigabits per second (Gbps) – or more than 11,000 times the average UK residential broadband speed. The idea is to improve scientists’ access to the results of LHC experiments.

A subsequent test in March using special equipment loaned by Nokia proved that the desired speeds were achievable.

“This transponder that Nokia uses is like a celebrity,” says Mr Verheul, explaining how the kit is reserved for use in various locations in advance. “We had limited time to do testing. If you have to delay a week, the transponder is gone.”

That amount of bandwidth, approaching a terabit per second, is extremely fast, but some undersea cables are a few hundred times faster still – they use multiple strands of fiber to achieve those speeds.

Image source, Nokia and Surfing

In labs around the world, networking experts are creating fiber-optic systems capable of sending data even faster than that. They are achieving extraordinary speeds of many petabits per second (Pbps), or 300 million times the speed of the average UK home broadband connection.

That’s so fast that it’s hard to imagine how people will use that bandwidth in the future. But engineers are wasting no time in proving that it’s possible. And they just want to go faster.

The duplex cable (with cores that send or receive) from CERN to data centers in the Netherlands is just under 1,650 kilometers (1,025 miles) long, snaking from Geneva to Paris, then Brussels and finally Amsterdam. Part of the challenge in achieving 800 Gbps was transmitting pulses of light over such a long distance. “Because of the distance, the power levels of that light decrease, so you have to amplify it at different locations,” explains Mr. Opdenakker.

Every time a tiny subatomic particle collides with another during experiments at the LHC, the impact generates staggering volumes of data – about a petabyte per second. That’s enough to fill 220,000 DVDs.

This is reduced for storage and study, but still requires large amounts of bandwidth. Plus, with an upgrade scheduled for 2029, the LHC is expected to produce even more scientific data than it does today.

“The upgrade increases the number of collisions by at least a factor of five,” says James Watt, senior vice president and general manager of optical networks at Nokia.

A time when 800 Gbps seems slow may not be far off, however. In November, a team of researchers in Japan broke the world record for data transmission speed when they hit an astonishing 22.9 Pbps. That’s enough bandwidth to power every person on the planet, and then a few billion more, with a Netflix stream, says Chigo Okonkwo of Eindhoven University of Technology, who was involved in the work.

In this case, a massive but meaningless stream of pseudo-random data was transmitted over 13km of coiled fibre optic cable in a laboratory environment. Dr Okonkwo explains that the integrity of the data is analysed after the transfer to confirm that it was sent as quickly as reported, without accumulating too many errors.

He also adds that the system he and his colleagues used relied on multiple cores — a total of 19 cores inside a fiber cable. This is a new type of cable, different from the standard ones that connect many people’s homes to the internet.

But older fibres are expensive to dig up and replace. Extending their lifespan is useful, argues Wladek Forysiak of Aston University in the UK. He and colleagues recently achieved speeds of around 402 terabits per second (Tbps) over a 50km-long optical fibre with just one core. That’s about 5.7 million times faster than the average UK home broadband connection.

“I think it’s the best in the world, we don’t know of any better result than this,” says Prof. Forysiak. Their technique relies on using more wavelengths of light than usual when sending data down an optical line.

To do this, they use alternative forms of electronic equipment that send and receive signals over fiber optic cables, but such a setup can be easier to install than replacing thousands of miles of the cable itself.

But reliability may be even more important than speed for some applications. “For remote robotic surgery over 3,000 miles … you absolutely don’t want any scenario where the network goes down,” says Mr. Creaner.

Dr. Okonkwo adds that training AI will increasingly require moving huge data sets. The faster this can be done, the better, he argues.

And Ian Phillips, who works alongside Prof Forysiak, says bandwidth tends to find applications when it is available: “Humanity finds a way to consume it.”

Image source, TeleGeography

While several petabits per second is far beyond what today’s web users need, Lane Burdette, a research analyst at TeleGeography, a telecommunications market research firm, says it’s impressive how quickly demand for bandwidth is growing — currently around 30 percent year over year on transatlantic fiber-optic cables.

Content delivery – social media, cloud services, video streaming – is consuming far more bandwidth than it used to, she notes: “It used to be something like 15% of international bandwidth in the early 2010s. Now it’s up to three-quarters, 75%. It’s absolutely huge.”

Andrew Kernahan, head of public relations for the Internet Service Providers Association, says most home users can now access gigabit-per-second speeds.

However, only about a third of broadband customers are subscribing to the technology. There is no “killer app” at the moment that really requires it, says Mr Kernahan. That could change as more and more TV is consumed over the internet, for example.

“There is definitely a challenge in getting the message out and making people aware of what they can do with infrastructure,” he says.