Nicolás Medina Mora on Mexico’s first female president and the country’s political future ‹ Centro Literário

Journalist and novelist Nicolás Medina Mora joins co-host VV Ganeshananthan and guest co-host Matt Gallagher to talk about Mexico’s president-elect, Claudia Sheinbaum, who will be the first woman and first Jew to lead the country. Medina Mora explains the history of current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, his hold on Mexico’s political imagination, and how his connections to Sheinbaum will affect the future of politics as he uses his final days in office to attempt 18 changes to Mexico’s constitution. Medina Mora, editor of the Mexican magazine Nexos, reflects on writing about López Obrador through fiction and journalism. He elaborates on a pre-election article he wrote for The New York Review of Books and also reads his novel, North Americain which he plays with the relationship between fiction and non-fiction.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews on the Lit Hub Virtual Book Channel, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube channel, and our website. This podcast episode was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Matt Gallagher: Claudia Sheinbaum was elected president of Mexico on June 2, and we were talking about her status as the first female president of Mexico and the first president of Jewish heritage. She is also a scientist who was previously Secretary of the Environment in Mexico City and had the support of the acting president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, better known as AMLO. We’ll get to Sheinbaum in a moment, but can you tell our listeners a little about AMLO, your shared party affiliation, and why he was such a beloved figure? Basically, how were things when the election occurred?

Nicolas Medina Mora: Of course, AMLO was elected president in 2018 with a landslide, not as big as Sheinbaum; Sheinbaum got 5 million more votes than him, which is truly remarkable.

AMLO campaigned as a leftist under the banner of a party he founded called El Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional, or Morena for short, and defeated candidates from the traditional parties that dominated Mexican politics during the first 18 years after the end of a -partisan government in 2000. An important thing to remember is that we didn’t really have democracy in Mexico until 2000. I remember the first democratic election, and AMLO campaigned as an outsider because he had left the traditional parties, but he had a long career in Mexican politics.

He was mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2006. And before that, he was a card-carrying member of the only party we had before, the authoritarian Party of Institutional Revolution, or PRI. And so he’s a complicated figure. I don’t doubt his leftist convictions when he governed Mexico City; he was a perfectly reasonable social democrat. He became well-liked and popular by approving welfare measures, such as old-age pensions, for the elderly. And in general, he rejected the traditional pomp and circumstance and, implicitly, the dishonor that people have come to associate with Mexican politicians. It would be driven in a Nissan Tsuru instead of an armored SUV, things like that.

And then he ran for president in 2006, and lost by less than a percentage point to the right-wing candidate, Felipe Calderón, and he and many of his supporters believed that fraud had been committed against him, electoral fraud. And so AMLO, at that time, became irritated with the institutions of what came to be known as the democratic transition, this period of moving away from the one-party state towards a very patristic democracy. And he kind of became bitter in a way, at least that’s my opinion.

As president, he remained extremely popular. He has approval ratings that, depending on the polls you listen to, range from 55 to 70%. But his policies as president were not always left-wing and sometimes, I think, frankly, reactionary. He gave power to the military. He refused to raise taxes. And so we arrived at the elections with a very popular president, who had discursively insisted that he was left-wing, but governed in a complicated way that we will talk about later. And he anointed as his successor: Sheinbaum, who was at the time mayor of Mexico City. And I think everyone thought she was going to win, everyone who was serious, but no one really predicted the extent of her victory, just the margin by which she won, we can talk more about that later, but I think it’s more or less that’s where things stayed.

VV Ganeshananthan: I didn’t know the margin was so big. So when I first read about Sheinbaum, I thought, “Oh, she’s a Jewish woman who’s also a progressive climate scientist! I can feel good about that! I would love some feel-good news! But in a play he wrote for The New York Book Review, which was published on April 7 before the election, you offered a much, much more complicated take on it, which I really enjoyed reading. I wonder if you can talk a little more about her background and her connection to AMLO that makes you think.

NMM: Of course, then Sheinbaum is the granddaughter of Jewish refugees who fled the Holocaust, on both sides of the family. She grew up in an upper-middle-class academic family in Mexico City. Her parents are also scientists and her upbringing seems to have been more leftist and secular than religious. There is a video of her that was circulated during her campaign, of her playing and singing this genre of leftist Latin American music when she was 8 or 9 years old, I forgot exactly how old she was.

And then she got into politics when she was a college student in Mexico, campus politics is different than in the United States, it’s much more about national politics than about the university itself, and she joined a group that later became the youth wing on the left. party that AMLO left to found Morena later. And there’s a photo of her protesting the North American Free Trade Agreement when she was doing graduate research at Stanford. So, she was involved in left-wing politics from a young age and throughout her life, and from very early in her career, she was linked to AMLO.

Her first public position, her first position in public life, was as Secretary of the Environment in the AMLO government in Mexico City. After that, she was elected head of the Tlalpan neighborhood in Mexico City, which is in the south of the city, which is kind of the neighborhood president in New York, so to speak, and later, when AMLO was elected president, she was elected mayor of Mexico City, her former perch.

And the reason her relationship with AMLO gives me pause is that, yes, Sheinbaum looks great in the role, and everyone I know who has worked with her holds her in high regard and thinks she shouldn’t be dismissed as a mere puppet of the president. But the problem is that the party they share is this set of contradictions. It’s like the Congress Party in India. It’s just this giant thing where there are all these different factions, it’s different in different regions, there are people who are pure communists and people who are just refugees from other parties that were destroyed by their electoral success. And the only thing holding it all together is loyalty to AMLO, at least so far. This could change.

So the problem is that you worry that Sheinbaum might, in part because she seems to sincerely believe in this man, and in part also because she needs him not to declare her a traitor to the country in order to govern effectively, so that she can’t be capable of deviating from some of its more, shall we say, reactionary policies. AMLO is obsessed with oil. There is an old platitude in Mexican politics in the 1930s that oil is the lifeblood of the nation, because the only socialist president of the old regime, Lazaro Cardenas, expropriated foreign oil interests, and for many years Mexico enjoyed truly remarkable economic growth, thanks to oil. That is no longer the case; the state oil company is completely decrepit.

But AMLO, however, has been building this refinery, this new oil refinery that cost an absurd amount of money and still hasn’t refined a single barrel. But leaving aside the confusion over the construction of this thing, one wonders who in their right mind builds an oil refinery in the year of Our Lord 2024? Given what we know about climate change, it seems completely suicidal.

So it seems like we’re facing this paradox: we just elected a climate scientist as president, and yet she’s unlikely to cancel this refinery or move away from this oil-first energy policy. Partly because, again, she seems to sincerely believe in AMLO and AMLO’s ideology, and also from a more pragmatic perspective, because she really can’t afford to alienate him. So that’s, I think, something that makes me think. We have a candidate, now president-elect, who has many things to like, but who will enter the National Palace in a context that will not necessarily allow her to govern in the way that, I think, her most progressive supporters expect her to do.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Keillan Doyle.

*

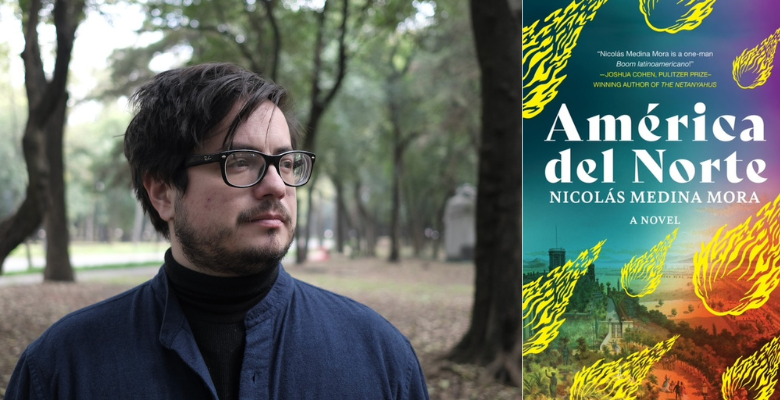

Nicolás Medina Mora

North America • What’s next for Mexico? | Nicolás Medina Mora | The New York Book Review • Nexos

Others:

Fiction/Non-Fiction Season 7, Episode 32: “Claire Messud on Confusing Family History and Fiction” • Fiction/Non-Fiction Season 7, Episode 17: “Ed Park on Family History’s Past, Real and Imagined Korea” • “Mexico’s outgoing president pushes ahead with plan to fire 1,600 judges” by Christine Murray | Financial Times • “The bloodiest elections in Mexico’s history send new asylum seekers to the US border” by Caitlin Stephen Hu, David Culver, Norma Galeana and Evelio Contreras | CNN • The Netanyahus by Joshua Cohen