Inserting science into Borderlands: inside the game, inside a game

In 2020, a new minigame appeared in the video game Frontiers 3located in the laboratory of the resident scientist on the spacecraft Sanctuary III. While the arcade game may seem like just another way to pass time in-game, the tile-matching puzzle game—Frontier Science—allowed millions of players to help map the human gut microbiome.

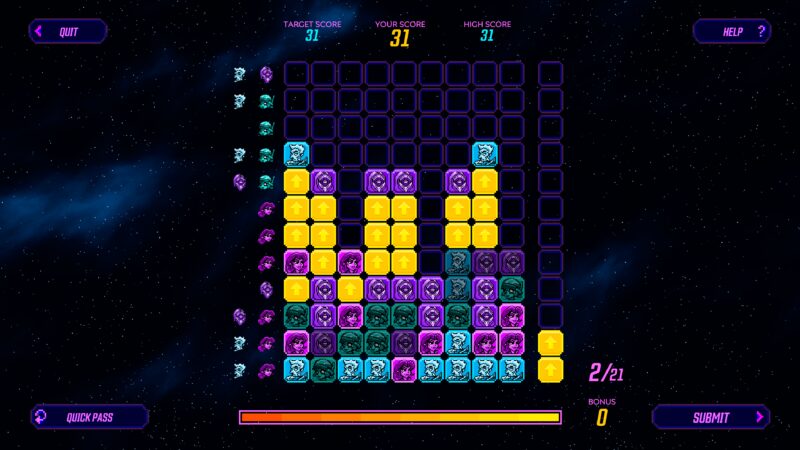

Frontier Science is one of the first examples of a citizen science game incorporated into a mainstream video game; it translates the correspondence of players’ blocks into the alignment of sequences of microbial DNA strands that encode ribosomal RNA. Ultimately, this could help deduce the genetic relationships between different gut microbes – crucial information for demystifying the complex web of interactions between diet, disease and the microbiome.

Since launch, over 4 million players have played Frontier Science, collectively solving more than 100 million puzzles, making this one of the largest citizen science projects of all time. Not only did the game generate enormous player engagement, but the results surpassed state-of-the-art computational methods, according to an analysis of the project published in Nature Biotechnology.

“We didn’t know if players of a popular game like Frontiers 3 would be interested or whether the results would be good enough to improve what was already known about microbial evolution. But we were impressed by the results,” Jérôme Waldispühl, a professor at McGill University and senior author of the paper, said in a statement.

Back to the drawing board

Often, citizen science games closely resemble the real scientific task being performed and involve discovering solutions to complex problems, such as optimizing protein folding in Fold it. While this has the potential to generate very useful results, the complexity can be off-putting and reduce player engagement and retention, restricting the audience to people with a prior interest in science.

Frontier Science takes a new design approach to try to overcome these challenges by breaking the overall scientific problem into several bite-sized puzzles. This is not as simple as it seems, as there is no “ground truth” with RNA sequence alignment, making it impossible to classify a puzzle solution as simply right or wrong. Instead, each puzzle makes a small contribution to optimizing an overall sequence solution.

This simplification, or gamification, means that people are more likely to engage with tasks, but even if a player only completes a few puzzles, it’s still useful. Compare this to Foldit, where if a player quits after tinkering with the protein structure for 10 minutes, nothing will be gained.

The successful modularization of the problem is one of the work’s key innovations, Sebastian Deterding, a professor at Imperial College London whose work includes citizen science games, told Ars. “As long as we have enough attention at the beginning, even if we only keep people for two or three puzzles, that’s enough.”

Additionally, the developers kept game design at the forefront, aiming to produce a game that, at its core, is simply fun to play. Gearbox Games, developer of the best-selling Borderlands franchise, carefully designed the minigame to fit seamlessly into the series’ distinctive art and atmosphere, including dialogue with existing characters so as not to break immersion.

A risk that paid off

Designing citizen science games is a balancing act between making tasks simple and fun enough to engage users, but complex enough to generate meaningful results. The simpler the task, the more people you need to involve to produce data. For Frontier Science, the hypergamification bet worked. Although the task was more gamified than any other citizen science game there has ever been, the enormous player engagement it generated more than made up for this simplification.

The game dramatically surpassed its predecessor, Phylumwhich is a free independent game made with a less gamified interface: “In half a day, the Frontier Science players collected five times more data on microbial DNA sequences than our previous game, Phylo, collected over a 10-year period,” Waldispühl said in a statement.

Although Frontier Science generated some excellent data and showed that integrating science into conventional games can work well. Deterding is skeptical about whether other teams will be able to adopt this approach.

“Sharing data with industry is very complicated and very dependent on you having a connection,” he told Ars. “It would be interesting if we could convince gaming entertainment companies that this would be a good corporate social responsibility initiative that more of them could and should do, and could do easily. But again, at this point, I think it’s a very fragile and precarious path.”

Nature Biotechnology, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-024-02175-6

Ivan Paul is a freelance writer based in the UK. He recently completed his doctorate in cancer research. He is on Twitter @ivan_paul_.