51,000-year-old Indonesian cave painting may be world’s oldest narrative art

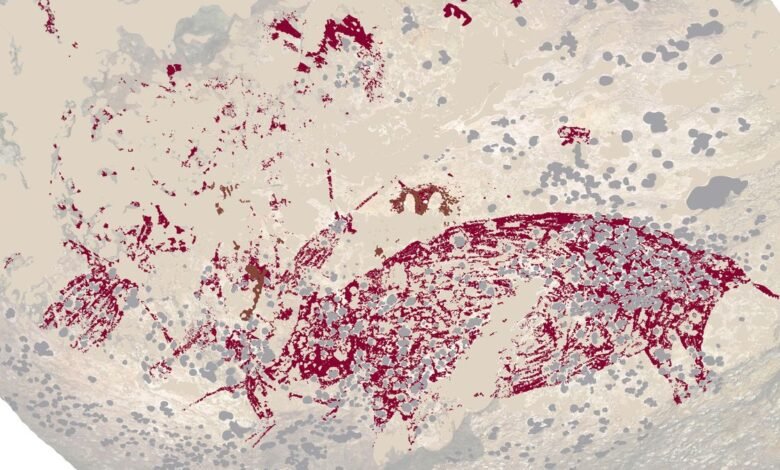

A cave painting on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi may be the oldest evidence of narrative art ever discovered, researchers say. The artwork, which depicts a human figure interacting with a warty pig, suggests that people may have used art as a way to tell stories for much longer than we thought.

Archaeological evidence shows that Neanderthals it started cave marking as early as 75,000 years ago, but these markings were typically non-figurative. Until a few years ago, the oldest known figurative cave painting was a 21,000-year-old cave art panel in Lascaux, France, showing a human with bird head attacking a bison. But in 2019, archaeologists unearthed hundreds of examples of rock art in caves in the Maros-Pangkep Karst. The rock art included a 15-foot-wide panel depicting human figures interacting with warty pigs (Sus celebensis) and anoas (Bubalus) — dwarf buffaloes native to Sulawesi.

“Storytelling is an incredibly important part of human evolution, and possibly even helps explain our success as a species. But finding evidence of it in art, especially very early cave art, is exceptionally rare,” Adam Brummco-author of the new study and an archaeologist at Griffith University in Australia, said at a news conference.

Archaeologists previously dated the panel’s rock art and found it to be at least 43,900 years old, while the oldest image they found in the area was of a 45,500-year-old warty pig.

Now, using a more sensitive dating technique, archaeologists have discovered that the cave art is at least 4,000 years older than previously thought, making it about 48,000 years old. More surprisingly, the archaeologists found a similar depiction of the human figure and warty pig in another cave in Leang Karampuang that was at least 51,200 years old, making it the oldest known narrative art. Their findings were published Wednesday (July 3) in the journal Nature.

Related: Did art exist before modern humans? New discoveries raise big questions.

Archaeologists were intrigued by narrative art’s depiction of a part-human, part-animal figure, or therianthrope.

“Archaeologists are very interested in depictions of therianthropes because they provide evidence of the ability to imagine the existence of a supernatural being, something that does not exist in real life,” Brumm said.

Previously, the oldest evidence of a therianthrope was the ‘Lion Man‘ sculpture unearthed in a cave in Germany.

“These depictions from Indonesia are pushing the dates back by almost 20,000 years, which is really groundbreaking,” he said. Derek Hodgsonan archaeologist and scientific consultant for REGISTERa European project investigating the development of writing, which was not involved in the study.

The early evidence of a therianthrope is a sign of complex human cognition, Hodgson told Live Science. “You don’t find any of these Neanderthals or ancient pre-human archaic species producing complex figurative art.”

To date the narrative art more precisely, the researchers used a technique called laser ablation uranium imaging.

Previously, scientists dated the cave paintings by carbon dating small samples of rock “popcorn” — clumps of calcite that accumulated over thousands of years.

But in the new study, Brumm and his team used even smaller calcite samples — just 0.002 inches (44 microns) long. By collecting much smaller samples, archaeologists get a higher resolution of the age distribution of calcite on the cave walls. The technique also minimizes damage to the artwork.

“This really changes the way we do recorded dating and can be applied to other records as well,” study co-author Renaud Joannes-Boyausaid a geochronologist at Southern Cross University in Australia at the press conference.

Although the identity of the painters is most likely Homo sapiensis a mystery, the lack of evidence of human occupation suggests that the cave may have been reserved for the production of art. The cave is hidden from the rest of the area at a higher elevation.

“It’s possible that people, these early humans, were climbing into these high-level caves just to make this art,” study co-author Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist and geochemist at Griffith University, said at the press conference. “Maybe there were stories and rituals associated with viewing the art, we don’t know. But these seem to be special places in the landscape.”

The team is planning to research and date more rock art in the area.

Recently, Adhi Agus OktavianaThe study’s lead author and an archaeologist at the Center for Prehistoric and Austronesian Studies (CPAS) in Indonesia, found a painting in another cave of three figures representing a human, a half-human, half-bird figure and a bird figure. But the team has not yet analyzed the painting.

“It’s very likely that there are more beautiful ones hidden somewhere that we don’t know about,” Aubert said.